Chapter Excerpt

This could be any village street. The packed dirt could cover any country road, and the dust that rises in billowing sheets, lifted by the lazy hands of the dry season, could menace any provincial town. It is three oclock in the afternoon, but no children wander back from school. The Chinese shopkeepers door has been shut for nearly a year, but no matter, since the children will not bother him for moon cakes, sweet wafers, and candied tamarind. A kalesa driver sits idly by his cart; his horse, unperturbed by the state of affairs, dozes behind blinkers, flicking rhythmically with his tail, one rear hoof casually cocked to bear no weight. In response to a fly, the horse shakes his head, jangling gear and whipping his mane from side to side. The fly rises up, buzzing at a higher pitch. What you are witnessing is war. A woman in a faded floral shift slowly makes her way down the sidewalk. She carries two huge woven bags; one is full of vegetables, the other holds a few canned goods and some dried fish, although a year ago this bag would have been full of meat. The woman has black hair, which she has pulled into a tight bun. Even streaks of gray (a new appearance this last year) break through the black. Her face is thin. She clenches her teeth with the effort necessary to carry her load. She sets down her bags, takes a deep breath, then manages a few more steps. The faded cloth of her dress is damp with perspiration. She wears a scarf wrapped around her neck, which must be uncomfortable in this heat. She sees the kalesa. She waves, then calls. The driver lifts his head. He was dreaming. The beautiful washerwoman was offering him a rice cake. The cake was blue. She was smiling at him with perfect teeth. "This is for you," she said. The beautiful washerwoman moved her hips from side to side. She smiled slyly. "Take the cake . . ." And then the sight of Mrs. Garcia waving at him down the street. She can barely manage. It is 1943. Imagine, a woman of such standing carrying her own groceries, there on the street, bareheaded in the early afternoon heat. Imagine all that gray hair, overnight, it seems. He closes his eyes again; sadly, the beautiful washerwoman is gone. He pulls himself to his feet. "Oo po," he shouts, although lazily, in Mrs. Garcias direction. Oo po = the polite greeting, but the driver manages to make it sound like an insult. What will she do, this woman? She isnt wealthy anymore. She is merely someone who was once wealthy, which is still worth something = she has held on to her house. He pats his horses dusty shoulder. What sentimental urge has made him keep Diablo alive? He knows the horse will be stew meat within a month or so. How can he feel sorry for his horse when his brother and little son are dead? It is easy to feel sorry for a horse, even easy to feel sorry for Mrs. Garcia, who has never had to carry b

This could be any village street. The packed dirt could cover any country road, and the dust that rises in billowing sheets, lifted by the lazy hands of the dry season, could menace any provincial town. It is three oclock in the afternoon, but no children wander back from school. The Chinese shopkeepers door has been shut for nearly a year, but no matter, since the children will not bother him for moon cakes, sweet wafers, and candied tamarind. A kalesa driver sits idly by his cart; his horse, unperturbed by the state of affairs, dozes behind blinkers, flicking rhythmically with his tail, one rear hoof casually cocked to bear no weight. In response to a fly, the horse shakes his head, jangling gear and whipping his mane from side to side. The fly rises up, buzzing at a higher pitch. What you are witnessing is war. A woman in a faded floral shift slowly makes her way down the sidewalk. She carries two huge woven bags; one is full of vegetables, the other holds a few canned goods and some dried fish, although a year ago this bag would have been full of meat. The woman has black hair, which she has pulled into a tight bun. Even streaks of gray (a new appearance this last year) break through the black. Her face is thin. She clenches her teeth with the effort necessary to carry her load. She sets down her bags, takes a deep breath, then manages a few more steps. The faded cloth of her dress is damp with perspiration. She wears a scarf wrapped around her neck, which must be uncomfortable in this heat. She sees the kalesa. She waves, then calls. The driver lifts his head. He was dreaming. The beautiful washerwoman was offering him a rice cake. The cake was blue. She was smiling at him with perfect teeth. "This is for you," she said. The beautiful washerwoman moved her hips from side to side. She smiled slyly. "Take the cake . . ." And then the sight of Mrs. Garcia waving at him down the street. She can barely manage. It is 1943. Imagine, a woman of such standing carrying her own groceries, there on the street, bareheaded in the early afternoon heat. Imagine all that gray hair, overnight, it seems. He closes his eyes again; sadly, the beautiful washerwoman is gone. He pulls himself to his feet. "Oo po," he shouts, although lazily, in Mrs. Garcias direction. Oo po = the polite greeting, but the driver manages to make it sound like an insult. What will she do, this woman? She isnt wealthy anymore. She is merely someone who was once wealthy, which is still worth something = she has held on to her house. He pats his horses dusty shoulder. What sentimental urge has made him keep Diablo alive? He knows the horse will be stew meat within a month or so. How can he feel sorry for his horse when his brother and little son are dead? It is easy to feel sorry for a horse, even easy to feel sorry for Mrs. Garcia, who has never had to carry b

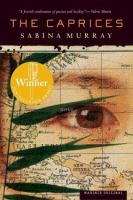

Excerpted from The Caprices

by Sabina Murray

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are

provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or

distributed without the written permission of the publisher.